Thane and Nagpur advance on climate resilience planning with completion of climate risk and vulnerability assessments

June 14, 2021

Urban-LEDS International Networking Seminar 2021: Reflecting progress and the importance of peer exchange among project stakeholders

September 7, 2021In South Africa, smaller municipalities are finding ways to fill the climate data gap prevalent across Africa and it is taking them a crucial step closer to accessing the finance they need for tangible, climate-forward projects.

Globally, cities are increasingly recognised as hotspots for climate change impacts and, in many places, key contributors to the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that contribute to it. It is crucial that these cities focus on adapting to the already-experienced impacts of climate change by identifying, prioritising and investing in climate adaptation measures tailored to their context. In order to do so, they need information about climate patterns impacting their specific city, historically and into the future. However, many countries in Africa lack access to quality climate information, and South Africa is no exception.

The lack of climate data, especially in South Africa’s small and medium sized cities, is cause for another major barrier: It is limiting these local governments’ ability to access the finance needed to take climate action. Robust climate data can help bolster project proposals for financing and put these cities in a better position to fund the projects that will not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but also build climate resilience to both expected and unexpected future shocks the city and its leaders might face.

Why climate data is lacking in South Africa’s smaller municipalities

Various South African institutions, including the University of Cape Town’s Climate Systems Analysis Group and the South African Weather Service, have established climate information systems that showcase historical and projected climate trends. Yet the level of engagement of climate data in South Africa remains limited and light, especially in smaller municipalities and towns.

Weather stations, while frequent in bigger cities, are often sparsely distributed in the rural areas, creating gaps in the data. Even if more weather stations existed, there is a lack of capacity at municipal level to process, analyse and embed the data into the city’s plans. Smaller municipalities in particular often lack the staff capacity and adequate knowledge to analyse simulated climate models and, without funding, they cannot appoint external service providers to do this. They also lack the mechanisms needed to mainstream the climate information into urban decision-making processes, ultimately considering this climate information when they make the decisions about the town’s future.

Local knowledge effectively filling data gaps in South African municipalities

In order for decision-makers in South African municipalities to mainstream climate data, they require climate information that covers their local jurisdiction in detail using formats they can easily understand and incorporate into their existing municipal decision-making processes and frameworks. This is proving to be a challenge, because there is often a disconnect between the type of data currently available and what subnational governments actually need. Existing climate information, which is usually relevant for bigger cities, needs to be downscaled to speak to the local context and smaller population.

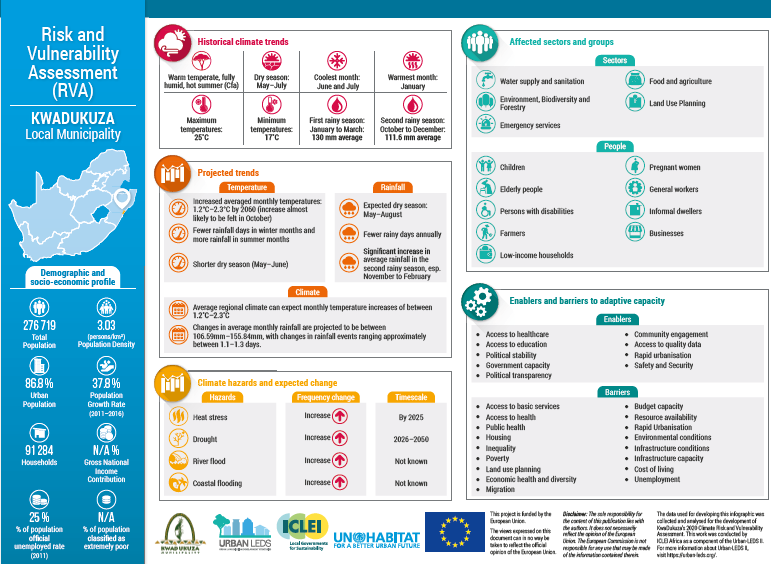

Through the Urban-LEDS II project, ICLEI Africa has been working with two South African municipalities to fill this gap. While collecting data to identify the climate risks and vulnerabilities in KwaDukuza and Steve Tshwete Local Municipalities, we consulted local residents and government officials to gain on-the-ground knowledge to complete and validate their Risk and Vulnerability Assessments (RVAs). The data was context-specific and based on local, historic knowledge, and arguably filled the gaps more effectively than if we were to use traditional data collection methods from information systems and downscaled it to apply to these towns.

It is widely known that the local residents know best when certain events took place and what the implications of those events were on their community’s livelihoods.

By creating infographics from both the Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventories (GHGI) and RVAs for these municipalities, officials can more easily engage with the often data dense reports to make decisions based on the city’s current reality and how climate change will impact it in the future.

KwaDukuza Local Municipality’s Climate Risk and Vulnerability Assessment developed using a combination of data from climate information systems and the knowledge of the local residents and government officials

Building metering provides energy data to reduce emissions and unlock climate finance

As part of their jurisdictions, local municipalities in South Africa own and manage a significant number of buildings and these have been found to be the key contributors to a municipality’s greenhouse gas emissions. It is therefore imperative that municipalities reduce their own energy demand to improve the resource efficiency of buildings and ultimately reduce the overall greenhouse gas emissions of these cities, towns and regions.

The first step is to undertake an energy audit to understand the current consumption. However, in South Africa, few – if any – buildings in municipal portfolios are metered. Because of this data gap, South African municipalities rarely receive financial support for increasing energy efficiency and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. A lack of robust energy data also reduces the quality of proposals for energy efficiency programmes that subnational governments typically submit to potential funders, further exacerbating the challenge of accessing finance.

Through a pilot programme of Urban-LEDS II, we took a practical approach by installing energy meters in municipal buildings of seven municipalities across the country. The project aimed to address these energy data and finance gaps:

- Improve the availability of energy data in municipal buildings by installing meters in at least three municipal buildings and one streetlight area for each municipality

- Build capacity of government officials in relation to energy management in municipal buildings by training up to 24 officials from participating municipalities to collect and analyse energy data

- Improve the technical skills of officials to submit bankable proposals to potential funders by developing application templates specific to each municipality to fund energy efficiency interventions

The project was a great success and shows potential for similar projects. Filling these data gaps will not only show municipalities how to reduce their own emissions, but also open the possibilities to future climate finance.

“By measuring, monitoring and reducing energy consumption, the municipality is able to release more funds to be used on other projects that are impacting the community as a whole. Because there are savings in one place, more money is available to spend on other areas such as the development of housing and other services delivered efficiently.”

Mr. Duma Nokubonga, Director, Electrical Engineering Services, KwaDukuza Municipality, KwaDukuza Local Municipality, South Africa

Download to read the full case study for the building metering pilot project.